Winner of the 2008 ESSENCE Literary Award for Photography —Essence Magazine

First published in 1982, Daufuskie Island vividly captured life on a South Carolina Sea Island before the arrival of resort culture through the photographs of Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and words of Alex Haley. Located between Hilton Head and Savannah, Daufuskie Island has since become a resort destination. Moutoussamy-Ashe’s photographs document what daily life was like for the last inhabitants to occupy the land prior to the onset of tourist developments.

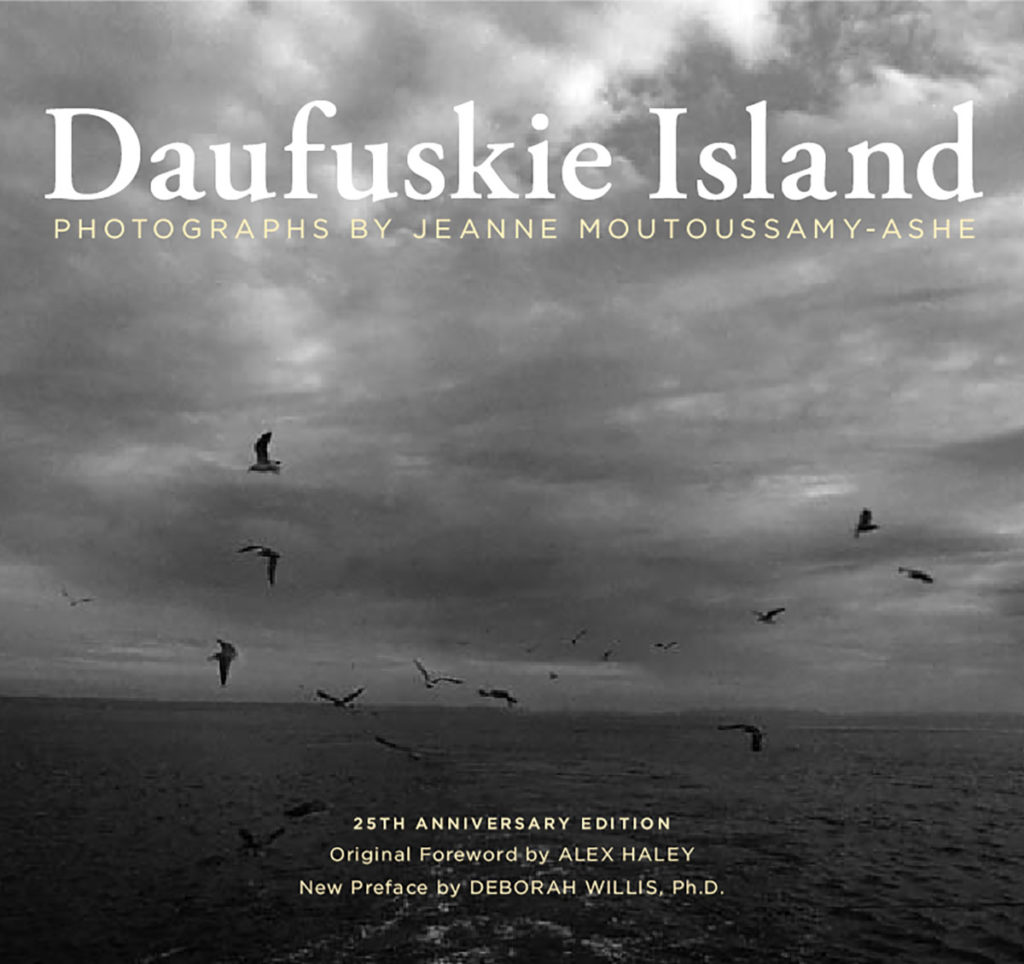

Redesigned from cover to cover, the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Daufuskie Island includes more than fifty previously unpublished photographs from the original contact sheets, a new preface by Deborah Willis, and a new epilogue by Moutoussamy-Ashe. This edition was published to accompany a traveling exhibition sponsored by Merrill Lynch.

Cover of the 1982 original Daufuskie Island: A Photographic Essay

“These photographs present a valuable picture of a culture that is rapidly vanishing. Paradoxically they also exist as a record of Daufuskie’s existence, hence its preservation.” ―Deborah Willis, from the preface

Daufuskie Island—the name means “land with a point” in the dialect of its original inhabitants, the Yamacraw tribe—lies just off the coast of Savannah, Georgia, about a 45-minute ride by ferry or a 25-minute ride by speedboat from the neighboring resort island of Hilton Head, South Carolina. From the end of the Civil War until it was developed into a resort property in the 1970s, Daufuskie Island was inhabited primarily by the Gullah/Geechee people, freed slaves and their descendants, whose distinctive language and culture remained strongly influenced by their African heritage. With no bridge to the mainland to this day and no electricity or telephone service until the early 1950s, the island’s residents lived in relative isolation from the rest of the world.

The photographs of Daufuskie Island are the culmination of an idea born while Moutoussamy-Ashe was on independent study in West Africa during college. Having photographed fishing villages, she stood at the porthole of the Cape Coast Castle in Ghana, the last stop for many enslaved people before embarking for the New World. Looking out at the vast, endless expanse of water and considering the horrors of the transatlantic crossing and the additional horrors that awaited enslaved people upon their arrival she decided to visit the terminus of that journey in the United States, the Southeastern seaboard and Sea Islands.

It took years of visits and many interviews for Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe to create these sensitive, intimate images of the people of Daufuskie Island—the last of the sea islands to be transformed by tourism and real estate development. Her images convey joy and dignity, while challenging our understanding of documentary photography. They reveal life in a dwindling community of African American people whose families had lived on these islands off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia since before the Civil War. The images evoke the shadows of change and the uncertainty that the islanders felt about development—their need for jobs, and the inevitable losses that would follow in the wake of the island’s transformation. Since these photographs were taken, properties have been sold, golf courses were built, and oyster fishing has vanished.

At the time the photographs in this book were taken, from 1977 to 1981, fewer than 84 permanent residents lived in the approximately fifty homes on the island and were served by a co-op store, a two-room school, a nursery, one active church and two active cemeteries. The year 1952 brought first electricity and then telephone service to the thickly wooded island, which had only dirt or sand roads, no fire department, no police, and no hospital or clinic. Residents experiencing medical emergencies beyond those a midwife could take care of were rushed by speedboat to Hilton Head. The Daufuskie islanders used little or no electricity, relied upon ox-driven carts for transportation and sent their children to be educated in the island’s only schoolhouse. They supported themselves as they had for centuries, fishing for oysters and growing cotton. After the boll weevil caused cotton crop failures and pollution ruined oyster beds, more and more residents sold their land to commercial developers.

The photographs represent a clarion call to preserve what remains of island life, and a harbinger of what is before us if we fail to act to preserve the culture of the rural south. The images document the lives of the island’s residents just before the tides of change swept over this once-remote community. In addition to paying tribute to the people and culture of the sea islands, the book serves as an important historical record of the last bastion of Gullah-Geechee tradition and unspoiled island life.